A recent study published in The Lancet suggests that falling fertility rates across nearly every country could dramatically shrink the world’s population by the end of the century. The study, from Washington’s School of Medicine, claims the global population will peak at 9.7 billion by 2064, before falling back to 8.8 billion by 2100.

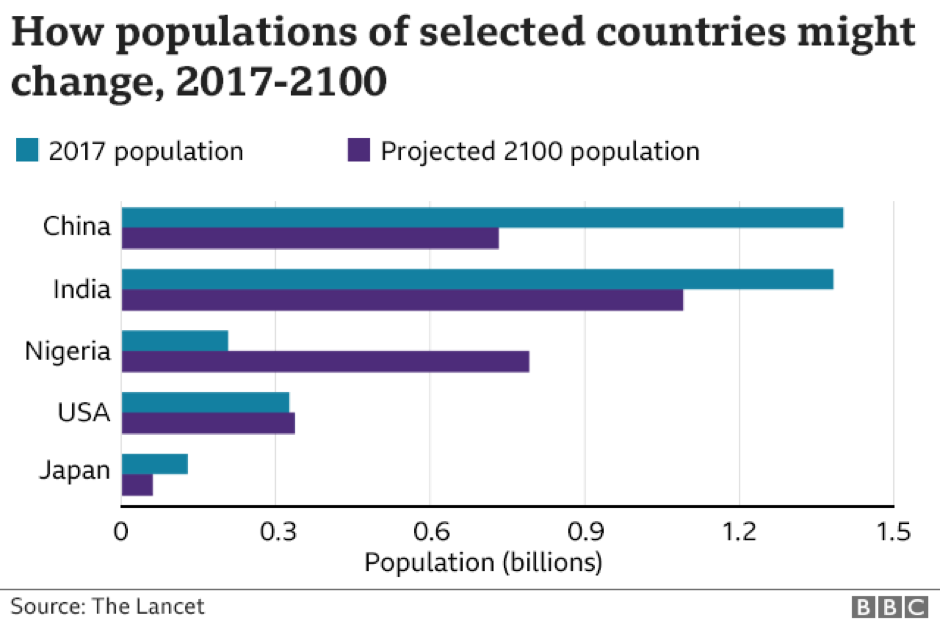

Keeping populations at ‘replacement’ levels requires a fertility rate of 2.1 births per woman – the average number of children a woman delivers over her lifetime. But by 2100, the study suggests 183 countries out of 195 will have a fertility rate below 2.1. A sustained period below this rate will see the population of countries, including China, Japan, Italy, and Spain effectively halve, while the population of sub-Saharan Africa could triple. We’re looking at a massive redistribution of the world’s population taking place in just 80 years.

Isn’t fewer people on the planet a good thing?

As women across the world gain greater access to education and contraception, many are choosing to have fewer children. On the surface, a reduction in the global population appears positive. However, while the number of children aged under five will fall from 681 million to 401 million by 2100, the number of 80-year olds will increase to a staggering 866 million. As a result, the next generation will be burdened with the care, and cost, of a much larger ageing population. A reduced workforce will not be available to produce tax revenues or corporate cash flow, money needed to pay for future retirees.

What does infant healthcare have to do with population decline?

Historically, healthcare innovation and ‘medtech’ have tended to be skewed towards the needs of the adult population. This makes sense, after all, healthcare professionals and the pharmaceutical industry have traditionally focused on taking care of the largest number of patients first. This mind-set was perhaps easier to justify while populations were booming, but faced with a future of fewer births, the long-term health of every baby is now more important than ever.

Good health begins at birth and impacts a generation

New global estimates show that in 2014, approximately 10.6% of all live births were preterm. Globally, prematurity is the leading cause of death in children under the age of five. And, in almost all countries with reliable data, preterm birth rates are increasing. As well as placing a heavy burden on healthcare systems, premature birth is associated with chronic diseases, disability and reduced cognitive function. These diseases, in turn, increase the chances of high risk pregnancies – creating a vicious cycle and increasing premature birth rates with every generation.

To break the cycle, we urgently need to start investing in new-borns. That means developing and supporting innovations in neonatal care that reduce mortality and prevent chronic disease – solutions designed specifically with the needs of infants at the centre, not at the margins.

Start at the beginning – not the middle

Most of what we know, and how we think, about neonatal healthcare has been adapted from adult medicine. Even the concept of the ‘golden hour’ – the name given to the first hour of post-natal life where medical interventions can help to create a better long-term outcome – was originally adopted from adult trauma management.

Most treatments and diagnostics currently being used in neonatal intensive care units were never originally intended for use in babies. A recent study suggested that up to 90% of neonatal treatments are considered “off-label”, because they were developed for adults. Extrapolating what we know about adult medicines – and using that to inform how we treat new-born babies – is fraught with danger. As one 2018 study put it: “The lack of information about the safety and efficacy of drugs increases the risk of poor clinical outcomes, of adverse drug reactions (ADR) and medication errors when off-label and unlicensed medicines are prescribed to neonates”.

Changing the standard of care begins with intelligent diagnostics

Diagnostics is the starting point for personalised and preventative medicine. By predicting disease in new-borns, we can intervene in that ‘golden hour’ to prevent many major complications, co-morbidities and disabilities. A critical starting point is respiratory care. Most premature babies are born with under-developed lungs which, if left untreated, often leads to respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in premature babies. RDS can be prevented with rapid diagnosis and treatment at birth. SIME is a digital diagnostics company using artificial intelligence (AI) and data science to help doctors intervene when it’s needed most, and in doing so, giving more premature babies a fighting chance.

Our test allows doctors to diagnose RDS, and administer Surfactant – one of only a handful of medicines developed specifically for new-borns – just moments after birth and within that critical, life-saving ‘golden hour’. Acting early has the potential to prevent severe respiratory disease, lessen the need for mechanical ventilation, and drastically reduce the amount of time spent in hospital. This is just one example of how digital diagnostics based on cloud-based machine learning can test for medical conditions and ultimately lead to better long-term outcomes, not just for the patient in the earliest hours of their life, but for society facing an uncertain future.

Invest in the future means investing in babies

The events of 2020 have shaken us out of our collective complacency, and the coronavirus has reminded us that there’s so much about life we do not yet know. Medtech and healthcare innovation has already been identified as a key investment trend for the next decade. The demand for digital solutions to help us fight some of the world’s greatest challenges is only going to increase, but we must begin by allocating resources more effectively.

It starts with acknowledging that, to invest in the future we have to invest in babies, which means prioritising their long-term health from the very beginning. Imagine what could be achieved if we shifted focus away from adult treatments and made greater efforts to learn from children instead? It could lead to new treatments and help us gain a better understanding of ourselves, medically speaking, through every life stage. The technology is there and, in many instances, already being developed – we just need more stakeholders to recognise the opportunity, get behind the ideas and help to bring them to life.

view article on medium